Published July 5, 2022

42 min read

Does the Title of “Queer” Still Promise a Radical Book?

Content warning for (other) uncensored homophobic language.

Note on terminology: Those familiar with my work may notice that I most often write “LGBTQ” over just “LGBT,” where here I elect to the latter. This is not to deliberately exclude or slight people who use the word “queer” to describe their same-gender attraction or transness, but more-so to illustrate how some usages of “queer” discussed here actively clash with association with LGBT identity. As I use the acronym “LGBT” throughout this text, it remains a stand-in for “not simultaneously cisgender and heterosexual,” regardless of personal labels or any other factors.Note on structure: While I do provide personal insight here, this piece is still ultimately at least 50% quotes. You’ve been warned!

“Queer,” for a plethora of reasons, is a complicated word. Weaponized against LGBT people as a slur for decades (and still today), groups of those within that demographic began self-identifying with it as an in-your-face counterattack, so to speak, during the AIDs crisis and onward. As the years went by, the word spread and evolved, becoming the name of a (virtually undefined) demographic, an intentionally vague sexual identity, a school of academic thought, and (presumably) a set of politics. All these uses share the assumed notion of radicalism that queerness is/was meant to represent. How well, though, did this string of letters keep that promise?

Many who currently identify with the word “queer” see it as a more inclusive alternative to supposedly “traditional” identities and coalitions, an inherently revolutionary force against societal norms. This is despite the fact that 1) words alone don’t do much to disrupt any system, and 2) “queer” often contradicts these ambitions, especially when looking at the past few decades of its history. In a few ways, it’s simultaneously expanded and watered itself down.

Modern Manifestations of “Queer”: Dreams of Inherent Progressiveness

Many people place “queer” on a pedestal of inclusivity, though this idea of inclusivity seems to exist as a hierarchy of desirability. There remain debates about whether bisexual women who date or prefer men, for example, are “queer enough.”

Quite a few LGBT people, both for and against “queerness,” act as though there’s an inherent difference between “gays” and “queers.” Some see “queers” as, generally, undesirably eccentric or excessively left-leaning, while others see the act of defying norms as inherently progressive and something we ought to do. Thus LGBT people who see themselves as normal, desire more “traditional” aspects of life like marriage, or otherwise (consciously or not) obey societal rules are practically accused of bootlicking. Michael Arceneaux, author of the memoir I Can’t Date Jesus (2018), revealed that “[s]omeone I was talking to was offended recently because I’d said I was gay rather than queer. It was like I was taking some assimilationist stance.”

I bristle at genuine political assimilation, dislike the marriage institution, and very openly loathe capitalism — but what we refer to as “the LGBT community” is a diverse demographic with varying individual beliefs and desires, not a political party. Associating “gayness” with intrinsic assimilationism and “queerness” with automatic radicalism, at best, seems to reflect a wish for many people to abandon their identity in favor of another they may have trauma with to keep true to their own politics.

At most realistic, it’s just naive and arguably homophobic, especially when being “gay” is still very much a controversial (and sometimes lethal) thing to be. If one truly cares about the issues that go unspoken in so-called “assimilationist” circles with which you share a demographic, space, and/or common goals, the solution isn’t just to abandon them and gain a superiority complex for picking up a new identity. And really, how much of a person’s politics can one glean purely from how they identify, especially if their politics are based on a different association of the words “gay” and “queer”? It’s not like everyone’s association with these words is identitcal — and there are plenty of cisgender heterosexuals with more radical politics than some LGBT people or even “queers.”

“Queerness,” due to its frequently-worn invisible badge that says “I’m revolutionary,” sometimes becomes a way to pass haughty judgment and even excuse or make bigoted sentiments. This causes LGBT spaces, often lauded as open-minded spaces, to be surprisingly unwelcome not only to those uncomfortable with the word but many LGBT people in general.

Charlie Manglas, a student (at the time) of Macalester College in Minnesota, writes about the harmful environment they encountered during their time in LGBT spaces on campus:

I dismissed the pit, which immediately materialized in my stomach at having a slur that I had learned to fear the same way that I feared the physical violence I associate with it, as culture shock that I would get over... Disliking the word [“queer”] was, it seemed, regressive... I quickly picked up on the views that I would have to adopt if I wanted any part in these communities. First of all, hating gay people is okay as long as you’re clever enough with the language you use to express that hatred. It’s perfectly acceptable, even encouraged, to yell about how you hate “monosexual queers” (i.e., people attracted exclusively to their own gender). [...]

We talk about not policing other people’s identities while non-consensually calling lesbians “queer women” or “homosexual homoromantics” (again proving ignorant of the violent, medicalized history of the h-word). [...] Above all, we talk about the importance of creating “safe but brave”* spaces while punishing those who publicly disagree with popular opinion. Vocalizing my discomfort with the unquestioned use of the slur “queer” as an umbrella term on campus led to me receiving anonymous hate and losing friends.

* Slightly related to the notion of “queerness as inherently progressive,” this phrase made me think of how unfortunate it is that people associate reclamation of a pejorative with bravery and the refusal to take part in that with cowardice. It ignores how it can also take strength to recognize how a word has hurt you, refuse to associate with it, and ask for acknowledgment of your pain and support.

Usages of “Queer”: Who Counts?

Ironically, while folks argue that gay men overwhelmingly have the most privilege in the community (please stop acting like their privilege comes from being gay), “queer” also seems to primarily signify that population at times. While the word is recognized as “as circulating in (at least) three distinct ways,” as Mark A. Gammon and Kirsten L. Isgro explain in “Troubling the Canon: Bisexuality and Queer Theory,” the first version proposed underlines its relatively restricted nature:

First, in many arenas “queer” is mobilized as a stand-in for the partnering of lesbian and gay. Which is to say, “queer” is often simply “invoked as style and symbol for homosexuality.” Originally proposed by feminist theorist Teresa de Lauretis in 1991 as a disruptive term intended to generate a critical distance from lesbian and gay, de Lauretis herself later renounced queer theory as “a conceptually vacuous creature of the publishing industry.” This first deployment of the term “queer” then offers a relatively narrow conception of sexual identity and has not typically provided bisexuals and other marginalized individuals, activities, or arrangements with a new or increased location within the realm of sexual politics. Queer Nation is one possible example of this use of “queer.”

This “first deployment” can be seen quite a bit in nineties literature, especially. Liz A. Highleyman’s “Identities and Ideas: Strategies for Bisexuals” notes that:

The position of bisexuals within the queer movement is unclear. Various groups and individuals disagree about just who should be included under the queer umbrella. Some maintain that “queer” applies only to gay men and lesbians (and perhaps gay- and lesbian-identified bisexuals who are willing to keep quiet about their other-sex attractions). In fact there may be a growing tendency for some gay men and lesbians to use the term “queer” to minimize the visibility of those who aren’t gay or lesbian — by using “queer,” they don’t have to mention bisexuals, transgendered people, and others by name.

A 1998 passage from “Fey Ways” by Tom Kwai Lam reads:

Yes, many faeries are bisexual, but more often than not are closeted about it. The male-only space of most gatherings — Stone Mountain excepted — precludes bringing one’s female lover to the gathering. Often, you are assumed to be gay or queer.*

*Considering that “queer” is also used separately from “gay,” it’s unclear what the former actually signifies in this context.

“Queer” was, to some people, a convenient method of erasure within LGBT communities. Despite the first iterations of the word in LGBT circles (outside of its context as a slur) often being strictly defined to mean “gay,” future definitions expanding upon the original may have also encouraged its use as a seemingly comprehensive term. This may have been a significant political setback for bisexuals, who were facing even more extreme forms of erasure in LGBT communities than we do today.

On the other hand, strangely, at the same time when “queer” was used rigidly, we also see people defining “queer” in broad ways that actively condemn terms like “gay,” “lesbian,” and “bisexual.” In a 1997 article interpreting the band Kraftwerk, Terre Thaemlitz writes this footnote:

The term “Queer”... is used as an alternative to identities such as Lesbian, Gay and Bisexual which operate in relation to the restrictive dichotomy of Heterosexual/Homosexual. As a reappropriation, the term “Queer” immediately discloses its contingency upon context. By de-essentializing sexual identities as social constructs through which people manifest their sexuality, rather than as immutable biological preconditions, Queerness places the construction of sexual identities within the social sphere, reinscribing their underlying cultural dynamics with the potential for social reform.

Frankly, the idea that bisexuality somehow complies with the binary that explicitly excludes it and denies its existence is rather odd. It’s possible that Thaemlitz conceptualizes bisexuality as a combination of straightness and gayness, an idea many bisexuals have been rejecting and discouraging for decades — but I digress.

Queer Theory

Known for frequent rejections of “traditional” sexuality and gender, many people laud queer theory as an intersection between radical politics and academics. Humorously, it has also sometimes argued that orgasming is regressive.

Queer theory has never regarded orgasm particularly highly. Despite some of the more notably orgasmic moments of early queer theoretical writing — one immediately thinks of Leo Bersani’s famous “image of a grown man, legs high in the air, unable to resist the suicidal ecstasy of being a woman” — many if not most of the texts and philosophers most ideologically fundamental to the development of queer theory have expressed profound skepticism about the political utility of orgasm. Michel Foucault and Gilles Deleuze, in particular, link “orgasm to the normalizing and striating strategies of modern power... characterizing it as an effect of the regulation and rigidification of sexuality,” thus “explicitly exclud[ing] orgasm from any repertoire of progressive practices.”

This isn’t actually relevant, to be fair — I just found it extremely funny.

Some of queer theory’s tenets, like theorizing human identity as socially constructed and questioning the concepts of normality and acceptance are undeniably valuable to liberation efforts. That said, some of its “revolutionary” edge remains performative. (Not to mention, the idea that academia exclusively uses formal terminology is simply wrong.)

In “The Normalization of Queer Theory,” David M. Halperin — who acknowledges that “queer” has been “routinely applied to lesbians and gay men as a term of abuse” — noted that de Lauretis coined “queer theory” as an applicator specifically to gay and lesbian studies, and it “originally came into being as a joke.”

Teresa de Lauretis coined the phrase “queer theory” to serve as the title of a conference that she held in February of 1990 at the University of California, Santa Cruz, where she is Professor of The History of Consciousness. She had heard the word “queer” being tossed about in a gay-affirmative sense by activists, street kids, and members of the art world in New York during the late 1980s. She had the courage, and the conviction, to pair that scurrilous term with the academic holy word, “theory.” Her usage was scandalously offensive. Sympathetic faculty at UCSC asked, in wounded tones, “Why do they have to call it that?” But the conjunction was more than merely mischievous: it was deliberately disruptive. In her opening remarks at the conference, Professor de Lauretis acknowledged that she had intended the title as a provocation. [...]

The moment that the scandalous formula “queer theory” was uttered, however, it became the name of an already established school of theory, as if it constituted a set of specific doctrines, a singular, substantive perspective on the world, a particular theorization of human experience, equivalent in that respect to psychoanalytic or Marxist theory. The only problem was that no one knew what the theory was. And for the very good reason that no such theory existed. Those working in the field did their best, politely and tactfully, to point this out: Lauren Berlant and Michael Warner, for example, published a cautionary editorial in PMLA entitled “What Does Queer Theory Teach Us About X?” But it was too late. Queer theory appeared on the shelves of bookstores and in advertisements for academic jobs, where it provided a merciful exemption from the irreducibly sexual descriptors “lesbian” and “gay.” It also harmonized very nicely with the contemporary critique of feminist and gay/lesbian identity politics, promoting the assumption that “queer” was some sort of advanced, postmodern identity, and that queer theory had superseded both feminism and lesbian/gay studies.

Here is a summarized collection of de Lauretis’ thinking. From this introduction to the theory, it’s evident that the “queer” in “queer theory” is neither meant as an LGBT umbrella term nor a term for gender and sexuality deviations apart from same-gender attraction. Furthermore, this queerness did not emerge from a desire to spite bigots via word choice.

As mentioned earlier by Gammon and Isgro, De Lauretis herself abandoned the phrase because the mainstream institutions that queer theory was meant to disrupt had taken it over.

“As for ‘queer theory’, my insistent specification lesbian may well be taken as a taking of distance from what, since I proposed it as a working hypothesis for lesbian and gay studies in this very journal, has very quickly become a conceptually vacuous creature of the publishing industry.” Distancing herself from her earlier advocacy of queer, de Lauretis now represents it as devoid of the political or critical acumen she once thought it promised.

Haperlin elaborates:

But with the institutionalization of queer theory, and its acceptance by the academy (and by straight academics), have come new problems and new challenges. There is something odd, suspiciously odd, about the rapidity with which queer theory — whose claim to radical politics derived from its anti-assimilationist posture, from its shocking embrace of the abnormal and the marginal — has been embraced by, canonized by, and absorbed into our (largely heterosexual) institutions of knowledge, as lesbian and gay studies never were.Despite its implicit (and false) portrayal of lesbian and gay studies as liberal, assimilationist, and accommodating of the status quo, queer theory has proven to be much more congenial to established institutions of the liberal academy. The first step was for the “theory” in queer theory to prevail over the “queer,” for “queer” to become a harmless qualifier of “theory”: if it’s theory, progressive academics seem to have reasoned, then it’s merely an extension of what important people have already been doing all [along]. It can be folded back into the standard practice of literary and cultural studies, without impeding academic business as usual. The next step was to despecify the lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, or transgressive content of queerness, thereby abstracting “queer” and turning it into a generic badge of subversiveness, a more trendy version of “liberal”: if it’s queer, it’s politically oppositional, so everyone who claims to be progressive has a vested interest in owning a share of it.

The ripping of “queer” from its historical context as an anti-LGBT pejorative and essentially transforming it into a vague descriptor for general “subversive” politics and thought processes can seem tone-deaf as is, but true irony resides in how eagerly the mainstream welcomed this version of queerness. Considering this, “it becomes harder to figure out what’s so very queer about it.”

Gammon and Isgro note after explaining the restricted version of queerness, however, that the second and third articulations of “queer” align more closely with the “non-normative” desires people express today. They point out that “queer” as a collective term potentially makes room for bisexuality and transness, and “queer theory and its politics seek to disrupt normative conceptions of identity as is typically practiced in both heterosexual and homosexual arrangements.” Yet the term doesn’t often succeed in doing either.

Queer theory, besides having its proposed subversiveness swallowed by academia, has often arbitrarily dismissed bisexuality and transness. “Playing with Butler and Foucault: Bisexuality and Queer Theory” goes in depth about how “seminal works of this theoretical school, written by authors such as Michel Foucault, Judith Butler, Diana Fuss and Eve Sedgwick, all bypassed bisexuality as a topic of inquiry even while writing against binary, biological models of gender and sexuality.” Michael du Plessis highlights in “Blatantly Bisexual; or, Unthinking Queer Theory,” how — despite queer theory claiming that identities aren’t static — bisexuals “are often accused of being too fluid to form or to ground a material politics.”

...a very different understanding of the term ‘queer’ operated in both academic circles and in some of the venues for ‘lesbian-and-gay’ journalism. There the term ‘queer’ functioned, as in Tendencies, to shut bisexuals either out or up. [...] Yet the bland belief that “theory” itself does not do a politics and does not produce an immediate practice can have very particular — if implicit — political goals, as the rumor about bisexuals not making good enough “theory” evidences... “theory” can be read as a pretext for biphobia and may operate in many situations as a straightforward act of elitism and exclusion.

[...] Because we are out of fashion, passé, a phase either passing or past, we are neither “theoretical” nor “queer” enough to be part of “queer theory.” We may look deconstructive, but we “[reinscribe] the very categories that bisexual identity claims to blur.” Our deconstruction, then, is a fake, an illusion, a lie, presumably like our sexualities and our identities, which are, in Solomon’s view, a “throwback.” Bisexuals must be discounted politically and theoretically: Solomon imagines politics and theory in separate realms at the very instant when “theory” is put to the political end of erasing bisexuality...

“The Politics of Inside/Out: Queer Theory, Poststructuralism, and a Sociological Approach to Sexuality” additionally discusses how queer theory frequently fails to acknowledge bisexual and transgender lives.

Some intellectuals believe that bisexuality is an impossible position. Interviewed in Outweek magazine[,] Eve Sedgwick [a founder of queer theory] claimed, “I’m not sure that because there are people who identify as bisexual there is a bisexual identity.”

[...] Queer theory has witnessed an explosion of essays on the subject of drag; yet it remains incapable of connecting this research to the everyday lives of people who identify as transgender, drag queen, and/or transsexual.Indeed, queer theory refuses transgender subjectivities even as it looks at them. The relation, as Sedgwick frames it, is one of “drag practices and homoerotic identity formations.” [...] Responding to the solipsistic character of queer theory, transsexual activists Jeanne B. and Xanthra Phillippa recently produced a button reading “Our blood is on your theories.”

[...] Interestingly, the shift from “gay/lesbian” to “queer” was intended to include bisexuals and transgenders. In the field of activism, this shift was marked by groups such as Queer Nation (QN). In the academy, “queer theory” has exhibited a tense relation to the very term queer. Teresa de Lauretis [who coined the term “queer theory”], for example, distances herself from the “queer” of QN [the LGBT queer] while most other scholars writing under the label consider only lesbian and gay subject-positions. The term queer has been ossified so quickly within the academy that bisexuals and transgenders must continually insist that it includes them.

A bisexual acquaintance of mine, Han, is currently taking a queer theory class (at a private Midwestern college), so I asked him to provide some contemporary insight by sharing his experiences. This is what he had to say. (Cut down and edited for length.)

We were once tasked with several “extra labor” assignments that we come up with on our own (within certain guidelines). One was just labeled “creative” and I decided to use my work with some bisexual peers on transcribing a bi magazine as an extra labor project. I wrote a 3-page reflection (as requested) basically pouring my heart out as to why this project — and my bisexuality — mattered to me. I had gotten the impression from others that my professor was extremely accepting and open, so I had no fear submitting such a personal piece.

The following class period just so happened to be a day where we discussed bisexuality, having read about the Darwinian history of the term. I was already anxious before class, but hopeful that my professor would guide the conversation in a positive direction. We were immediately put into groups (this is an online Zoom class thanks to COVID) and told to discuss our opinions on how bisexuality is viewed today. I was in a group with two other students, both of which expressed some sort of negative perception.

One girl was nice about it, simply saying that she doesn’t agree with the modern view of it as a phase, but that most people around her see it as something younger girls identify as to seem cool. The other girl went on and on about how her freshman year roommate decided to “experiment” with girls by flirting with them for fun. Ignoring the possibility that her roommate was genuinely interested in exploring their sexuality, this student was insistent that she was doing it to seem cool and that she was “actually just straight.”

I was shaking at that point. I mentioned I was bi really quickly before we were sent back to the main group — they were very uncomfortable after that.

Going back to the main call, we were asked to share our thoughts. Some people spoke about the reading, but then my professor started making offhanded comments about how she didn’t know how negative bisexuality was. For the rest of the class, she kept just talking about how no one likes the word ‘bisexual.’ I genuinely felt ill. I had just had conversations about my sexuality with her and submitted a very personal piece about bisexuality, and here she was spending our class shitting all over my identity. This is the same (cis and straight, mind you) woman who goes on about the need for inclusivity and acceptance in the “queer” community.

One really fun [sarcasm heavily implied] time was when a classmate, before giving their thoughts on the topic at hand, declared in a dismissive and slightly disgusted tone how bisexuals are “not queer in any way, like at all” and my professor just chuckled in reply.

We also have this interesting note from “Denormatizing Queer Theory: More Than (Simply) Lesbian and Gay Studies”:

[S]ome queer theorists have done exactly what Cherry Smyth warned against: continually substituted queer for gay. While lesbian feminists, such as Sheila Jeffreys, worry that queer theory is proving harmful to lesbian identities, many queer theorists fear that queer will be emptied of its political valence and critical edge if it is moved outside the gay and lesbian sphere.

There seems to be a very odd conflict afoot. While queer theory was practically formulated on denouncing categories it deems “binary” — especially “gay” and “straight — it’s often reluctant to let them go or even fully acknowledge terms besides “queer” that fall outside these proposed dichotomies (or consider that queer/normal is, too, a dichotomy).

Outside of this, though, queer theory simultaneously often has little to do with being LGBT. On multiple occasions, queer theorists — including two of the founders — have said their work is wholly unrelated to the LGBT usage of “queer.” Instead, the theory overwhelmingly uses the “abnormal” definition and routinely rejects the identities that reside in the LGBT acronym. Sometimes the abnormalities stay within the realm of sexuality (not necessarily orientation), but more often speak of non-normativity in a general sense.

From “Saint Foucault: Towards a Gay Hagiography”:

Queer is by definition whatever is at odds with the normal, the legitimate, the dominant. There is nothing in particular to which it necessarily refers. It is an identity without an essence.

From “What I Have to Say about Queer Theory”:

As Leo Bersani eloquently complained in his book Homos, queer theory is “de-gaying.” It isn’t about lesbians and gays; it’s about everyone confined by ideas about sex — that is, everyone, period.

From “Punks, Daggers, and Welfare Queens: The Radical Potential of Queer Politics?”

These [queer] theorists presented a different conceptualization of sexuality, one which sought to replace socially named and presumably stable categories of sexual expression with a new fluid movement among and between forms of sexual behavior.

A dominatrix would be “queer” under queer theory because she undermines the traditional sexual role of female submission. An award-winning article, “Drone Disorientations: How ‘Unmanned Weapons Queer the Experience of Killing in War,” discusses how drones “warp the norms” of warfare because their distance methods still allow the drone operator to be up close and personal with their victims. “The McElroy Brothers, New Media, and the Queering of White Nerd Masculinity” proposes that the McElroy brothers show “how nerds queer contemporary masculinity discourse... [their podcasts] reconstruct a nerd masculinity that does not pine for hegemonic masculinity as nerd media of the past.”

Queer theory’s conception of “queerness,” again, revolves simply around warping norms. Looking at how often the “queer” in “queer theory” has been little more than a synonym for “gay” and how many other times it hasn’t been about sexuality or gender at all, the theory itself adopts a paradoxical state, which is simultaneously the goal and proof of conceptual self-defeat.

Han adds:

A student mentioned them possibly being nonbinary only for someone else to rant about how “rigid” all identity labels are and dismissing this person’s experiences. My Professor did nothing to get this student to stop talking and instead went on a little tangent of her own about how “nonbinary is not a pretty word,” and whenever she hears it, all she can think of is how the word “just doesn’t sound nice.”

My Professor talks often about how queer represents the abnormal. She believes that “queer” encompasses all that do not fit society’s norms, including examples like “a cishet punk rocker who is anti-capitalist.” She asks us questions like “do you think this character is gay or queer?” and “do you think they are a lesbian queer-identified person?” Our assignments also frequently request we go “beyond gender and sexuality” when we look at queer theory as if those subjects don’t have merit.

There’s arguably a fundamental problem with the way queer theory continuously treats many marginalized identities as outdated and “normative” purely because they appear to be part of a binary categorization. The existence of the gender binary doesn’t necessarily make womanhood standardized; more often, it is accepted only so far as it complies with (and never questions) standards set by men. Simply because a sexuality binary exists does not mean that gayness fits, let alone upholds, any societal standard. Gayness remains criminalized, demonized, fetishized, pathologized, and scrutinized in countless ways.

The idea that gayness and straightness, manhood and womanhood, any combination of oppressor and oppressed, are merely two sides of the same repressive coin with equal power to rule over those with more “revolutionary” or otherwise non-dichotomous identities is incredibly devoid of nuance — especially when the scrutiny and violence most oppressed people endure is partly due to their perceived position as “opposite” to their oppressor (i.e., part of the dichotomy).

No identity label (identity in terms of describing senses of self, like “black” or “woman,” not identities like “republican” or “feminist,” which explicitly serve to describe political views) is or should be considered inherently politically advanced. Such terminology doesn’t intrinsically describe political ideology or anything other than how someone understands their existance in society. Assigning morality to otherwise neutral (even if considered old-fashioned) self-descriptors is to engage in political discourse that assigns descriptions of one’s personhood with unjust assumptions. It essentializes these identities, even if using “progressive” language.

While the political need for identity within society clearly exists, as there are currently oppressed identities (which are certainly not exempt from criticism), engaging in politics that seek to step outside these dichotomies just to create new ones only recreates the oppressive actions towards marginalized identities. Our collective goal should instead be on destroying these systems entirely.

This behavior seems to rely on an ironically neoliberal understanding of how sociological identities are exploited. People seek new, “better” hierarchies to position themselves in and adopt a label that, despite its subversive connotations and aesthetics, can’t inherently fulfill any promises.

Given how respected “Drone Disorientations” was, we can extrapolate that queer theory often has little interest in criticizing imperialism or its contributing forces. Thus it lacks the motivation to understand the different systems that force certain identities to adopt inferior societal positions as a means of capitalist and imperialist exploitation. At times, queerness only brings yet another system that people must prove their worth to, rather than the system trying to prove its worth to the people.

People who defend the wide use of “queer” purely because “that’s what academia uses” are quite odd to me. Besides the fact that academia outside of queer theory has also extensively treated LGBT people as diseases to be cured — medical institutions have thoroughly “studied” us without our consent for centuries — universities do not have the authority to determine how we exist. To take cues so eagerly from such institutions, especially if one argues that “queer” is an inherently radical word, seems rather counterintuitive.

Queer Politics

Cathy J. Cohen’s “Punks, Daggers, and Welfare Queens: The Radical Potential of Queer Politics?” provides interesting critiques, from a nonwhite perspective, on not only the lack of intersectionality in queer theory but the sometimes counterintuitive nature of — despite its clear benefits in certain areas — the approach of queer politics.

Despite the possibility invested in the idea of queerness and the practice of queer politics, I argue that a truly radical or transformative politics has not resulted from queer activism. In many instances, instead of destabilizing the assumed categories and binaries of sexual identity, queer politics has served to reinforce simple dichotomies between heterosexual and everything “queer.” An understanding of the ways in which power informs and constitutes privileged and marginalized subjects on both sides of this dichotomy has been left unexamined.

[...] Whether in the infamous “I Hate Straights” publication or queer kiss-ins at malls and straight dance clubs, very near the surface in queer political action is an uncomplicated understanding of power as it is encoded in sexual categories: all heterosexuals are represented as dominant and controlling and all queers are understood as marginalized and invisible. Thus, even in the name of destabilization, some queer activists have begun to prioritize sexuality as the primary frame through which they pursue their politics.

[...] In its current rendition, queer politics is coded with class, gender, and race privilege, and may have lost its potential to be a politically expedient organizing tool for addressing the needs — and mobilizing the bodies — of people of color. As some queer theorists and activists call for the destruction of stable sexual categories, for example, moving instead toward a more fluid understanding of sexual behavior, left unspoken is the class privilege which allows for such fluidity.

Class is indeed important here, especially when noting how some LGBT identities — like “butch” and “fem(me)” — are largely working-class identities. Historically, fems were typically the breadwinners because butches, who often took the role of physically protecting lesbian communities, couldn’t find employment.

Were butch and fem(me) roles often strict and expected in mid-twentieth century communities of woman-loving women? Sure. But to say this is inherently so or that the fact that the roles exist at all is somehow conservative, let alone a “replication of heterosexuality,” as some put it, ignores their context and history. Ironically, the idea that butch/fem(me) is outdated or regressive did not spring up in the 1990s; lesbian feminists (not to be confused with feminists who are lesbians) in the 70s also denounced butch/fem(me) as being archaic and even oppressive. In fairness, however, whether these two instances of condemnation are connected to each other in any way is unknown and probably unlikely.

Queer theorizing which calls for the elimination of fixed categories of sexual identity seems to ignore the ways in which some traditional social identities and communal ties can, in fact, be important to one’s survival. Further, a queer politics which demonizes all heterosexuals discounts the relationships — especially those based on shared experiences of marginalization — that exist between gays and straights, particularly in communities of color.

Considering how massively race influences and shapes gendered (and thus sexuality) experiences and ideals (due to colonialism fabricating our modern gender binary and roles), ideologies and politics that ignore this are routinely alienating for people of color as they disregard the nuance race brings into otherwise privileged classes. Black masculinity is deemed predatory and violent, for example, which is why many black feminists dislike (white) feminists who gloss over the racial aspect of the patriarchy and the fact that white women often have privileges over men of color.

But like other lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgendered activists of color, I find the label “queer” fraught with unspoken assumptions which inhibit the radical political potential of this category. The alienation, or at least discomfort, many activists and theorists of color have with current conceptions of queerness is evidenced, in part, by the minimal numbers of theorists of color who engage in the process of theorizing about the concept. Further, the sparse numbers of people of color who participate in “queer” political organizations might also be read as a sign of discomfort with the term. Most important, my confidence in making such a claim of distance and uneasiness with the term “queer” on the part of many people of color comes from my interactions with other lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgendered people of color who repeatedly express their interpretation of “queer” as a term rooted in class, race, and gender privilege. For us, “queer” is a politics based on narrow sexual dichotomies which make no room either for the analysis of oppression of those we might categorize as heterosexual, or for the privilege of those who operate as “queer.”

[...] It is not the nonheterosexist behavior of these black men and women [dependent on state assistance] that is under fire, but rather the perceived nonnormative sexual behavior and family structures of these individuals, whom many queer activists — without regard to the impact of race, class, or gender — would designate as part of the heterosexist establishment or those mighty “straights they hate.”

It’s fascinating to see such a strong clash between how queer academics (the field’s founders being overwhelmingly white) and activists interpret queerness and how others — especially those who would be considered “queer” in the theoretical or political sense — describe it.

In 1993, Peter Drucker gave a talk on queer nationalism further revealing that at times, not even queer movements founded on sincerely radical ideals realized that not every “queer” person has privileges outside of the context of sexuality.

Much more serious is the fact that for all the talk about inclusiveness, Queer Nation groups have been overwhelmingly white and male... [...] People of color have in fact been made to feel literally unsafe in Queer Nation meetings. Issues of racism and sexism have been key to Queer Nation splits in several cities. Wherever clear anti-racist and anti-sexist perspectives do not prevail, queer nationalism’s potential will continue to be wasted.

The problem unfortunately goes far deeper than insensitivity. The very definition of “queerness” tends to exclude lesbians, people of color, working people and people with disabilities. “Queer” oppression is seen as based on a consciously chosen and crafted identity. This “chosen” aspect of lesbian/gay oppression, the penalties put on explicit lesbian/gay self-expression, does exist and is important — this distinguishes lesbian/gay oppression from oppression based on race, gender or disability, which are generally not chosen but visible, material and unavoidable — but it is only one aspect of lesbian/gay oppression.

[...] The clearest expression of the idealist side of queer nationalism has come from the academic growth industry of “queer theory[.]” Although most Queer Nation activists know little about queer theory and understand less, queer theory has taken inspiration from queer nationalism and theorized some of the latter’s less positive attitudes.

Queer theorists have tried to make queerness inclusive by stressing that “difference” is integral to queerness, while “gayness,” they imply, is inherently uniform, white, male and middle class. But this attempt to valorize “difference” in fact minimizes it, making “queerness” the central issue of oppression and liberation, while lumping together gender, race, disability and class as particular elements that can be combined into a unique, creatively constructed identity.

[...] Queer nationalism, radical as it is, is sometimes strikingly moderate, as for example when the New York queer magazine QW endorsed Clinton for president. As Berube and Escoffier noticed, queer nationalists sometimes put great emphasis on the importance of being “recognized by mainstream society.” In the same issue of Out/lo[o]k, Maria Maggenti noted behind queer nationalists’ anger “an underlying desire, an unspoken yearning it seems, to be accepted instead of liberated.”

The same issues Drucker pointed out in the 90s exist today. I’ve interacted with self-proclaimed “queer” spaces both online and off — the casual racism, biphobia, transphobia, and even plain old homophobia wasn’t rare in the slightest.

As Alex V. Green notes in “‘Queer’ as in... what, exactly?,” self-proclaimed queer spaces often house the same issues which people criticize “less radical” gay spaces for.

Anyone who’s lived among self-described queers knows that our communities are often riven with racism and transmisogyny. There are many places in my city — and, if the conversations I’ve had with people in New York, Philadelphia, Montreal, Baltimore, L.A., San Francisco, and Vancouver are any indication, in many others as well — that call themselves “queer” or “queer-friendly” that are still hostile to people of color, poor people, trans people, women, and those with physical disabilities. Similarly, there are many “queer spaces” where the majority of the clientele on any given weekend are white men, many of them predatory. Several of my lesbian friends have stories of dudes leering down their shirts at ostensibly queer bars or queer-friendly events, trying to offer them drinks or drugs, following them around all night, or even threatening them with physical violence.

Green wonders if the usage of “queer” to communicate difference “simply reduces the many raced, classed, and gendered differences between so-called ‘gay’ and ‘queer’ spaces and communities to the terms themselves, rather than connecting them to the dynamics that produce those spaces and communities as such.” Our intra-community problems don’t begin or end at our labels or even our politics. Is this an inherent problem with the word “queer”? Not necessarily — though it provides a convenient shield for addressing intracommunity issues such as hostility towards other marginalized groups.

“Queer and...?”

Many people use the supposed universality of “queer” and how it can apply to larger groups instead of individual identities (which on its own is desirable) as a short-cut to social progression. They use a word to signify inclusivity without actually taking any steps or care towards making spaces and discussions safer for the otherwise marginalized. In doing so, they go back and turn a word with a supposed larger application into a much narrower concept.

People who use the word often tend to do so in ways that show it isn’t so complete after all. Possibly the most notorious example is the phrase “queer and trans(gender).” Considering how many people praise “queer” for being all-encompassing, this combination is annoyingly common. Why?

Most likely because we largely promote associations with that word with sexuality, not gender (unless you literally tack the word “gender” onto it to create the identity “genderqueer” — for the record, I have no issue with this label). If you say someone’s a “queer man,” you’ll likely assume he’s gay or bisexual. A number of straight transgender people don’t consider themselves exclusively “queer” because its primary connotation is still, in fact, “not straight.”

The way the word has been used for the past few decades as an inverse of (and even outright enemy of) heterosexuality ostracizes straight transgender people even more blatantly, even though transness disrupts heteronormativity just as much as same-gender attraction. Many cisgender folks complain about “straight people” even though few straight transgender people systemically benefit from their attraction.

This discrepancy in connotation was inevitable since we didn’t always have language to distinguish transness from non-heterosexuality, thus we historically used to just share terms like this, but we moved on from conflating “gay” with “transgender” a while ago. Thus there could still be problematic undertones with saying “queer and transgender people” and “queer community” in the same breath while acting like they’re equivalent. At the very least, I find it important to at least make up our minds on where transness stands with queerness.

Speaking of norm-breaking, it’s interesting to note that — while LGBT identity is inherently societally disruptive — quite a few LGBT people are not the biggest fans of seeing themselves as excessively divergent or anomalous since our heterosexist society routinely weaponizes this idea against us. Of course, that’s why many have reclaimed it, but this ultimately means that a term advocated for deviance will always inherently exclude (and likewise shame) anyone uncomfortable with seeing their attraction or gender journey as something that needn’t be gawked at like a new alien species.

Plessis additionally touches upon how “queer” separates itself from other identities.

Bisexuals appear in the introduction to Tendencies in a particularly torturous sentence which juxtaposes and contrasts “the moment of Queer (sic)” with “other moments” (Sedwick’s emphasis.) “[P]eople [who organize] around claiming the label bisexual, the steady increase in AIDS-related deaths, Clinton’s impending presidency, and the ‘massive participation by African Americans and Latinos’ in the New York Gay Pride Parade” are all part of the “other moments” which are set off from the “Queer” moment by Sedwick’s use of parentheses and italics, almost as if the text needed to differentiate typographically between what is “Queer” and what is not. Why are African Americans, Latinos, and bisexuals all shuffled off from the center of queerness here? Are there no people of color who are queers or bisexuals or even bisexual queers?

Phrases such as “gay and queer men” appear more than occasionally today, as they occasionally did in the late twentieth century. Even if one deems “gay” a bourgeois label (can we please stop acting like identity labels are indicative of one’s politics?), how does it not constitute as “queer” at all? Is gayness too “normative”? What’s queer and what’s not is hotly debatable, and the line seems to be drawn in a different place with each person you ask.

Dangers arise when attempting to quantify the queerness of an identity that’s already non-cisgender or non-heterosexual. Routinely grouping them all under “queer,” while not fundamentally problematic, sometimes births the incentive to measure how deviant from the norm people are. After all, everyone’s experience varies. Still, it shouldn’t be a competition.

Quantifying queerness and establishing borders between its degrees quickly descends into self-righteousness, as seen by gay people accusing bisexuals of heteronormativity or pansexuals frequently boasting about how “enlightened” they are compared to those who aren’t. It produces out-groups within an out-group, where people brush off certain LGBT people and experiences because they aren’t “queer enough.” It replicates the pecking orders of the outside world (e.g., men feeling the need to prove their masculinity to other men), pressuring those within “queer” spaces to prove they’re worth being there.

Oddly, the scale of perceived queerness here still isn’t consistent. There are arguments for gayness being “queerer” than bisexuality due to gayness’ lack of different-gender attraction (and the assumption that “bisexual” is not a full identity), while others claim that bisexuality is “queerer” than gayness because it incorporates attraction to more genders and blurs the line between gay and straight. Is being both a man and a woman (thus challenging the notion that the two genders are mutually exclusive) “queerer” than being agender (not participating in the gender systems at all), or vice versa? Why are questions like these ever being asked? How many rules must one break in order to be seen as a true radical, if that’s the goal here?

Going back to Highleyman’s essay on LGBT and queer identity, we see further examples of “queer” used in a manner that suggests an idea in some way disconnected from LGBT identity.

Others insist that queerness has a large ideological component — it is as much about how you think and what you believe as it is about what you do in bed or who you do it with... Still others think of queerness as a cultural construct, which includes specific types of dress, body piercings, genderfuck, and certain types of music. The evolution of the concept of “queer” has had a reciprocal effect on the concept of “straight.” If “queer” implies radical politics and sexual and social liberation, then “straight” implies conservative or reactionary politics, boring whitebread culture, and a resistance to sexual and social diversity. Thus it is possible to speak of such seemingly oxymoronic concepts as a “straight homosexual” or a “queer heterosexual.”

While LGBT identity and politics primarily focus on sexual orientation and gender, this instance of “queer” is simply an identity that is not normative in one way or another. The problem here, though, is that such queer identity is solely a matter of stating that you’re non-normative without much expectation to live up to it in any tangible way or even specify what norms you’re allegedly defying, let alone in what ways. No real specification seems present regarding what (broken) norms would constitute queerness. If one can excuse my silly examples, does “defying the dominant ideology” include things like participating in the scene subculture, following a different religion than your country’s official one, or committing petty theft?

All the ways in which people use “queer” means that any discourse around who and what counts as queer is primarily reliant on individual interpretations of multiple conflicting and often poorly (if ever) defined meanings of the same word and the politics given to each. While this is a fascinating and seemingly unique phenomenon, it often gets cumbersome and unproductive.

The primary contemporary definitions of “queer” are 1) “LGBT” (though primarily just “not straight”) and 2) “non-normative.” They get mixed up so often, however, that people argue that certain groups containing heterosexuals — asexual or polyamorous individuals, for example — can actually never be straight (even if they want to identify that way) because they’re “queer” (as in contradicting a societal expectation), and “queer” also means “not straight.” That said, one could also argue that lack of attraction isn’t necessarily the non-normative aspect, but rather adopting “asexual” as a deliberate “queer” identity. I digress.

The third meaning of “queer,” then, is almost a mixture of the other two. It’s an identity intended to be in the same family as things like “lesbian” or “agender,” but focused on being a (relatively undefined) socially deviant individual on which one’s actual sense of self is built upon afterwards. We could say this third meaning is a manifestation of “queer” as a political statement of anti-normativity, but made into an essentialized title. Interestingly, essentialism and rebellion are practically mutually exclusive.

Has Queerness Been Co-Opted?

As exhibited many times already, people often extend “queer” to specific groups deemed non-normative, even though they’re not at all exempt from benefiting from heterosexism. I’ve witnessed a cisgender heterosexual couple say, for instance, that having the man stay home and watch the children “queers” their relationship (even though parenting as a parent should be the bare minimum).

Considering that many people still view “LGBT” and “queer” (in terms of identities the terms contain, i.e., the non-cisgender and non-heterosexual) as entirely interchangeable — since it’s been a slur against us for lifetimes—this presents, among other problems, a false equivalency.

It’s arguably unhelpful to treat things like “women paying the bill on the first date” as though they’re on par with engaging in (same-gender) relationships or sex acts still punishable by death in quite a few countries. “Queer” would, as it does in queer theory, no longer refer solely to an oppressed class, but rather anyone who interprets themselves as going against a norm, regardless of how relevant it is to any axis of oppression or even discrimination, let alone LGBT oppression.

If we say that queerness refers not explicitly to LGBT identity but toying with gender and sexuality expectations in any fashion, would cisgender heterosexuals who date bisexual or transgender people be queer? Or tomboys? How solid of a basis does a pedophile or necrophiliac have in their argument for their alleged queerness? — this question may seem unfairly extreme, but it happens staggeringly often when we refuse to define the word or what we mean by “nonnormative.” (It may be important to note that some of the first queer theorists, especially Michel Foucault and Guy Hocquenghem, have openly defended pedophilia. While this isn’t indicative of the culture around queer theory as a whole, to say such ideas have never touched the theory is foolish.)

When queerness is no longer a matter of heterosexism, it’s an even larger problem when “queer” seems to grant instant social immunity against accusations of anti-LGBT bigotry. “I can’t be biphobic,” some may insist, “I’m queer myself!” Well, “queer” as in “attracted to similar and different genders? or “exclusively same-gender attracted”? Or “transgender”? Or “polyamorous” or “gender-nonconforming” or “dyed my hair an unnatural color”?

While many tout the excessive vagueness of “queer” as best attribute, we can’t avoid the fact that allowing a word’s meaning to expand indefinitely without any sort of borders removes any meaning that string of letters could possibly have.

Something that a number of self-identified queer people insist is that the pushback over the explosive increase of the usage of “queer” is a recent phenomenon or something only present in younger LGBT people, but this simply isn’t true. This dissatisfaction has existed for as long as Queer Nation has been around. In “Queer Today, Gone Tomorrow,” published in Diva Magazine circa the 90s, Emma Healey (also author of Lesbian Sex Wars) writes:

I call myself a lesbian (oh my god, I’m sounding ’70s) because I do not want my sexuality to be [a] fashion accessory, an academic exercise, a performance piece of theatre... Queer has commodified and commercialised itself to the point that it is now utterly disposable. It is time to take the pieces we find useful and throw away the packaging.

Stephanie Fairyington discusses in “The problem with co-opting ‘queer’” how, although a number of LGBT elders fully support self-proclaimed queerness in all its forms, cisgender heterosexuals identifying as “queer” often “doesn’t sit well with some older generations of LGBT people, who also bristle at the ever-expanding proliferation of identity constructs.”

While I appreciate the goodwill and solidarity of cisgender heterosexual males and females self-identifying as “queer,” it befuddles an already murky term, given the vast array of things it can mean, including gay, lesbian, bisexual, transgender, pansexual, gender queer, bigender, asexual, agender, nonbinary, asexual, (literally, the list can go on forever and ever), which dilutes its power and renders it almost meaningless.

[...] A 53-year-old cisgender lesbian I spoke to who lives in New Jersey likened calling oneself queer after reaping the privileges of being straight to former NAACP leader Rachel Dolezal, a white woman, calling herself black. “I have compassion for oppressed people of all kinds and I can genuinely feel for, say, black women and their particular struggles, but I can’t say I am ‘black.’ That would be silly and offensive,” she told me.

A 43-year-old New York City-based cisgender gay man I interviewed agrees: “It’s disingenuous to call yourself queer (given that it still popularly signifies someone who is L,G, B, or T) if you’ve never experienced the ostracism that goes with that,” he wrote to me via email. (Both interviewees asked to remain anonymous given the controversial nature of the debates around identity politics within the LGBT community.)

[...] While I too support the desire to collapse hierarchies and bust binaries to be more inclusive and reflective of people’s lived realities, I’m not sure a muddled mash-up of identities is an effective way to politically mobilize... Seventy-eight-year-old lesbian historian Lillian Faderman continues to find it jarring when LGBT people of her generation self-identify as queer. “Many men and women of my generation are repelled by the word ‘queer.’ Nothing is going to redeem that word for us because we were so wounded by it in the 50s,” she told me. Fellow historian Jonathan Ned Katz, the 81-year-old author of several books on gay and lesbian history, drove home Faderman’s point in a recent telephone interview. “An old friend who’s in his mid-80s has recently disowned me because in passing, I referred to ‘a queer art show.’ He was deeply, deeply angry and offended and finds it a put-down,” he said.

It would indeed make sense for older LGBT people to feel increased discomfort with the word “queer” as they lived through a time where they only knew it as harrowing, the thought of using it themselves being outrageous to even think about. Many young people have no idea about such history and are naturally more inclined to use it liberally. This isn’t necessarily bad; generational gaps will do that to ideology.

But on the topic of co-opting, one must ponder how queer theory, in particular, was such a catalyst for bringing that word into popular usage outside of violence and activism, to the point where it’s practically everywhere today. Although the sexuality of Teresa de Lauretis isn’t easily found (if present in any literature), another founding theorist, Eve Sedgwick, was known in academic circles as “the straight woman who does gay studies.” Regardless, one must wonder how appropriate of a move dubbing it “queer theory” was, even if it was an intentional juxtaposition, or if de Lauretis considered that bringing such a loaded word into academia would sterilize it.

Frankly, I believe that most of the problems that many people — including me — have with the word “queer” would be nonexistent if it at least stayed within the context of being LGBT, and people used (or even coined) a new term to describe a “non-normative” umbrella. The complex and often contradictory nature of the word “queer” is genuinely fascinating and could even prove useful, but it also seems almost mutilated in how it’s been treated and adopted in so many ways. I suppose it’s neither here nor there at this point.

Closing Thoughts

Ignoring controversies, I think there’s more to this issue regarding the nature of its usage. “Queerness” often operates on the notion that same-gender attraction, transness, and gender-nonconformity are innately strange. That, in turn, depends on our current framework: our patriarchal, white supremacist, heterosexist society that defines social ideals and standards. What happens when they all go away?

Unlike other parts of being LGBT, “queerness” (in the “not a cisgender heterosexual” sense, at least) directly describes the deviation from society’s cisgender, heterosexual standards. Some argue that this deviation isn’t exclusive to LGBT people; gender-nonconformity, for instance, can be performed by anyone, no matter who they are. Phrases like “queering fashion,” “queering marriage,” “queering heterosexuality” (remember, transgender heterosexuals exist) “queering” something, exist to explain how certain people defy how society demands people conduct and view ourselves. To (be) “queer” in this sense is to deviate.

As LGBT people, we deviate from the standards that our society uses to deem us subhuman. But if we tore down the systematic barriers preventing us from true freedom, this thinking would be null. None of us would be going against the grain of society because we’d be the grain; that, or there just wouldn’t be a grain at all. Can we truly be outsiders forever?

When people are supposedly fighting for the “right” to identify as a slur (reclamation doesn’t require permission), how does that benefit them? Does the word “queer” hold the same power when cisgender heterosexuals now use it “respectfully” towards us without knowing if we’re okay with it? When people lump in systematically oppressed experiences with just being “slightly out of the ordinary”? When it feels safer to say than “lesbian” or “bisexual”? When it’s risen to the status of pop culture and gets endlessly marketed by otherwise apathetic — if not actively hostile — corporations? When it’s practically the default term in academia, used to describe anything from threesomes to imperialist warfare? How useful or subversive is it now, really? Are we still taking back what we’re practically being given? Why do some insist on simply “queering” institutions instead of destroying them?

Of course, many people calling themselves “queer” don’t want to be seen as normal to begin with. Many LGBT folks value challenging the concept of normality, pushing boundaries, and self-expression. We embrace countering the society that sees us as nuisances due to our differences in thinking and living—I smile in my head when some days I look androgynous enough to watch a stranger truly rack their brain figuring out what the hell I am. So to become part of what’s considered normal may seem undesirable or even treacherous for some. At times, it seems like it’s less about taking back a word used against us or fighting oppression and more about just trying to stand out.

It’s inevitable that we as people will sometimes (or always) rebel against social norms no matter what they are, but queerness seems to have domesticated itself quite dramatically, especially with those who insist the word “queer” isn’t an anti-LGBT slur. To claim this while claiming it’s still radical is ironic at best. It isn’t possible to advertise a concept as both sanitized and revolutionary at once.

It’s either a hip, non-threatening alternative to other LGBT identities, an umbrella term for even the slightest of gender and sexual transgressions, or a word with a brutal history which those of us existing outside of the cisgender heterosexual world decided to yank from our oppressors and make our own. I know which sounds more radical (and accurate) to me. It’s rather unfortunate that people today often resist the notion that “queer” should even be considered a loaded or uncomfortable term.

From personal experience, quite a few steadfast champions of “queer” academia and politics I’ve encountered don’t even hold the anti-assimilation politics that radical queer activists typically do. Instead, they look at calmer routes — same-sex marriage, micromanaging identities, praising media representation even when it’s outrageously bigoted — as progress. The average person calling themself “queer” today isn’t necessarily doing anything else particularly radical. The label becomes a decoration.

When one adopts a word with a legacy of violence, it just seems odd to advocate for our community to participate in the very institutions that forcibly make us queer in the first place. Can we even say “queer” is intrinsically politically engaged anymore when people casually use it to refer to even LGBT multimillionaires? Even when people try politically reclaiming the word in similar veins as Queer Nation first did, it rarely truly works or even gets noticed anymore, because it’s been so defanged by forced reclamation and letting cisgender heterosexuals and corporations use it freely.

Many young folks championing the slur today have arguably made it lose its value outside of historical context. It’s become painfully mainstream, reduced to a mere aesthetic of radicalism rather than anything else, which is truly unfortunate. Quite honestly, if queerness hadn’t turned into this painfully ironic haven of bigotry, historical revisionism, and diluting our actual defiance, I don’t doubt for a second that I — as well as many others — would reclaim and identify as it. (In fact, I quite enjoy the term “genderqueer.” I only hesitate to identify with it full-on because, for obvious reasons, most people who call themselves this clash aggressively with my beliefs about the word “queer.”)

Plus, I already use other homophobic slurs for the same reasons some who reclaim “queer” do: as an act of implementing societal disobedience into one’s identity. It’s an acknowledgment that society sees us as a menace and taking pride in actively being one. It’s a rather pleasurable manifestation of spite.

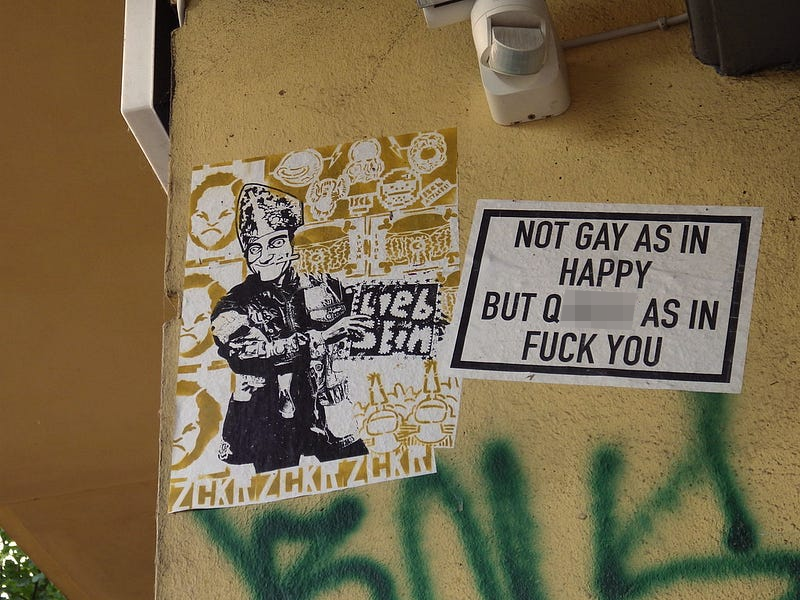

So I completely empathize with folks who cry out, “you can pry ‘queer’ from my cold, dead hands!” I still think “not ‘gay’ as in ‘happy’ but ‘queer’ as in ‘fuck you’” is a pretty genius tagline. But I must side with Healey when she observed decades ago that queerness has sold itself into oblivion. It can only be an aggressive identity if we preserve its original (aggressive) political intent. Pacifying it the way many do so today fails that task miserably. I personally would rather use a word that, while lacking the rougher history that slurs do, still stirs discomfort in people due to clearly unfinished political business with it (e.g., “bisexual” — dear god, do people hate this word).

Even if the connotations behind queerness weren’t at all an issue, one word still can’t do the hard work of radical politics that most self-proclaimed queer people align themselves with, and forcing it onto others is anything but revolutionary. In the words of Green, “our work must go beyond the assertion of difference, the demand for inclusion, and the desire to be part of something that seems important. It has to be motivated by a commitment to undoing the systems of political and moral policing that make ‘normal’ possible.”

I don’t see the title of “queerness” itself as an inherent issue. My qualms lie in that this word simply doesn’t magically solve the issues people think it does. Sometimes it just masks them when not outright creating new ones. We should acknowledge the word’s history, prioritize the vulnerable, combat the hegemony and discrimination in self-described queer spaces, and focus less on making “queer” versions of existing harmful institutions and more on dissolving them. A prison with an all-transgender staff and a rainbow painted on the side is still a prison.

I’d like to close with what Cohen states in her own concluding pages:

In the same ways that we account for the varying privilege to be gained by a heterosexual identity, we must also pay attention to the privilege some queers receive from being white, male, and upper class. Only through recognizing the many manifestations of power, across and within categories, can we truly begin to build a movement based on one’s politics and not exclusively on one’s identity.

I want to be clear that what I and others are calling for is the destabilization, and not the destruction or abandonment, of identity categories.” We must reject a queer politics which seems to ignore, in its analysis of the usefulness of traditionally named categories, the roles of identity and community as paths to survival, using shared experiences of oppression and resistance to build indigenous resources, shape consciousness, and act collectively. Instead, I would suggest that it is the multiplicity and interconnectedness of our identities which provide the most promising avenue for the destabilization and radical politicalization of these same categories.

[...] This is not an easy path to pursue because most often this will mean building a political analysis and political strategies around the most marginal in our society, some of whom look like us, many of whom do not. Most often, this will mean rooting our struggle in, and addressing the needs of, communities of color. Most often this will mean highlighting the intersectionality of one’s race, class, gender, and sexuality and the relative power and privilege that one receives from being a man and/or being white and/or being middle class and/or being heterosexual. This, in particular, is a daunting challenge because so much of our political consciousness has been built around simple dichotomies such as powerful/powerless; oppressor/victim; enemy/comrade. It is difficult to feel safe and secure in those spaces where both your relative privilege and your experiences with marginalization are understood to shape your commitment to radical politics. However, as Bernice Johnson Reagon so aptly put it in her essay, “Coalition Politics: Turning the Century,” “if you feel the strain, you may be doing some good work.”