Published Mar 17, 2022

22 min read

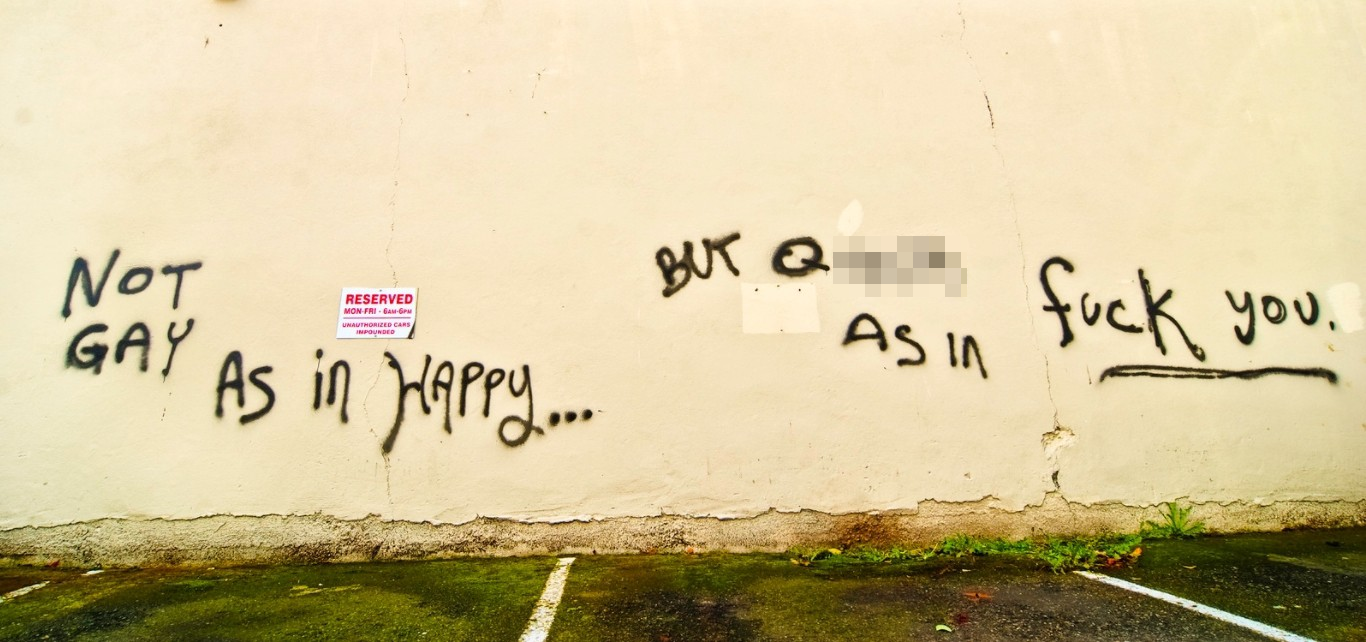

“Queer” Is Still a Slur

Content warning for (other) uncensored homophobic language.

Most understand “queer” as a synonym for “LGBT.” The word appears in virtually every place where “gay,” “lesbian,” “bisexual,” “transgender,” or just “LGBT” already is. Academia uses the word widely when discussing LGBT people and identity, and with shows like Queer Eye, it’s effectively an element of pop culture. The LGBT acronym often extends to LGBTQ (which I myself typically use in writing, with the exception of this article), where “Q” refers to “queer” or “questioning”.

Many outspoken LGBT individuals reclaim “queer” or even refer to their sexuality exclusively as “queer,” which they have every right to do. However, there’s also a growing insistence from some that it’s a superior, more inclusive alternative to other labels, and they’ll actively call other LGBT people “queer” by default. I find it odd and disrespectful, considering its history — and current usage — as a slur. It’s even more peculiar that some deny this entirely.

Preliminary disclaimers

“Saying ‘queer’ is a slur is T(W)ERF rhetoric”

Despite this being arguably the first attempt at a counterargument people jump to, this specific claim doesn’t come with much evidence, and few who claim this are actually transgender women. It’s an issue that people have practically stripped “T(W)ERF” (i.e., Transgender [Woman]-Exclusionary Radical Feminist) of its meaning, effectively derailing many conversations about transmisogyny and leading to some transgender women being called T(W)ERFs for having opinions contrary to the person making the accusation.

“T(W)ERF” doesn’t just mean “someone who is ‘exclusionary’ in certain areas.” It is an acronym specifically for radical feminists who politically exclude transgender women from their feminism and concept of womanhood. Biological essentialism is their ideological basis; nothing else is guaranteed of an individual T(W)ERF.

This is not to say that there’s no recorded history of T(W)ERFs speaking out against the concept of “queer politics,” but as we’ll see later on, disliking the word “queer” itself is not an original practice, and the list of reasons T(W)ERFs give for hating the word never starts and stops at “it’s a slur.” (After all, many lesbian T(W)ERFs proudly reclaim “dyke” precisely due to its similarly inflammatory nature.)

The earlier-linked article, for example, denounces many “queer women” not only for their occasional acceptance of transgender people but also their participation and encouragement of sadomasochism and pornography, their inclusion of bisexual women in the concept of lesbianism, talking openly about sex, and not being completely “anti-male.” Presumably, a game of telephone happened in the past decade or so where some people came to the conclusion that the sweeping claim that “queer is a slur” is a T(W)ERF idea, rather than gathering that the reasons they give for not liking the word — which isn’t inherent to the word or people who call themselves queer — are radical feminist rhetoric (which they sometimes are).

The most frequent theory I see online is that T(W)ERFs push the idea that “queer” is a slur to get younger people to reject terminology that includes transgender people, but this leaves much to be desired when

- younger people who aren’t repulsed by us will already include us in even more general terms like “(wo)man” and advocate for this inclusion,

- “LGBT” — which literally includes “trans” in the acronym—and its longer-lettered variations are still the most common way by the general public to refer to the general demographic of people antagonized by heterosexism, and

- people don’t commonly associate the word “queer” specifically with trans people (most who do are homophobes who simply view trans folks as “super” gay). Its primary use has always been to describe sexuality, hence people see the need for phrases like “queer and trans.” Few straight trans people exclusively identify as queer (i.e., queer but not trans), and a number of other trans people do not feel explicitly included in it.

Not even all T(W)ERFs today dislike the word — some identify as queer themselves (hell, some identify as nonbinary). There are many recruiting tactics and dog whistles T(W)ERFs use, but this is simply not one of them. As a transgender female friend, Maria (name falsified for privacy), put it:

Just because a lot of TWERFs happen to say that doesn’t mean they were the first. A lot of people who aren’t reactionaries — including a lot of trans women and older LGBT people — believe it’s a slur, too. It’s like claiming that “the US government is bad” or “democrats suck” is fascist rhetoric just because a lot of right-wingers also happen to say that. People reach conclusions for different reasons, and there are plenty of obvious differences with how they think about that idea.

A transfeminine acquaintance of mine, Bahiti (name falsified for privacy):

I think the idea that “queer is a slur” as inherently radical feminist rhetoric is ridiculous. I’m living proof that isn’t the case; I don’t regularly interact with radfems. It feels like a method to shut down argument rather than an actual talking point. If the idea comes from the fact that radical feminists aren’t comfortable with the word either, so what? Many of them are gay or bisexual, of course some of them will dislike it. Just because we agree on one thing doesn’t mean we do any other time. A broken clock is right twice a day.

Never mind the very real possibility that the agreement on this one singular idea is based on differing contexts. I am aware of the dangers of the patriarchy, as are they. The difference is that I don’t blame those dangers on “infiltrating males” or whatever.

Context matters, and a radical feminist talking point sounding like something I agree with is not enough to justify ignoring the concept as a whole. It simply shows one has not done enough thinking on the matter. To those who oppose the idea that it is a slur, do not compare me to my enemy.

“Saying ‘queer’ is a slur is USA-centric”

Language and the usage of certain words vary around the world. In Russia, most people aren’t familiar with the word “queer,” and those who are familiar are typically also LGBT who found it in the Anglosphere. It’s additionally employed as an umbrella term in some other non-English-speaking countries. However, these usages are 1) obviously divorced from the history it has in the United States and the harm it often carries in English (not a bad thing, but it’s nonetheless the case), and 2) only happening because it was used in English first (after all, it’s an English word).

We could argue that calling “faggot” or “dyke” slurs is also USA-centric, but the usefulness of such conversations is debatable; some words can and do have different weights depending on location (e.g., “cunt” is far ruder in the USA than Australia).

If English-speakers started using “maricón” or “pédé” (the Spanish and French equivalents of “faggot”) as a catch-all for gay and bisexual men and tried to make it acceptable for public usage by anyone, that still wouldn’t make these words no longer slurs. “It’s not a slur in English” doesn’t kill the argument because it’s not even a word in English, even if we adopt it. They would still be words from another language used to describe the same people they target in the original language.

Etymology and Current Usage

The word “queer” emerged from 16th century English, meaning “strange.” Some other early definitions include “physically sick,” “eccentric,” and “worthless.” The earliest documented use of the term to describe an LGBT person was in 1894 by John Sholto Douglas, a Scottish nobleman. He wrote a letter to his son, Lord Alfred Douglas, blaming the “corruption” and death of Francis, his other son, on “snob queers” like Archibald Primrose, allegedly in a relationship with Francis during his lifetime.

In the early- and mid-20th century, “queer” began to be used by gay men to identify with traditional masculinity, unlike the effeminate “fairies” at the time. In America, “queer” first appeared in print in a Los Angeles Times article detailing the 1914 trial of Herbert N. Lowe, who was accused of having gay sex at two private clubs. From then on, the word was associated primarily with sexual deviance, effeminacy, and men in same-sex relationships.

By the 40s, “queer” declined in acceptability within the gay male subculture once the concept of “homosexual” identity arose. In the coming decades, “queer” was interchangeable with other homophobic epithets like “fairy” and “faggot.” Flamboyant men were “the predominant image of all queers within the straight mind.”

In some mid-twentieth century lesbian communities, “…‘queer’ [was] the language of those who came out in the 1950s, particularly at the end of the decade,” but — along with the term “homo,” for those who came out in the 40s — “had derogatory connotations, implied stigmatisation, and were used somewhat ironically, the former is more clinical, and the latter more judgmental…”

Amidst the 80s AIDs crisis, some LGBT people once again started taking the slur back for self-identification, this time with a much clearer political intent. The organization Queer Nation formed in 1990 and circulated a flyer called “Queers Read This,” containing this passage:

Ah, do we really have to use that word? It’s trouble. Every gay person has his or her own take on it. For some it means strange and eccentric and kind of mysterious… And for others “queer” conjures up those awful memories of adolescent suffering. queer. It’s forcibly bittersweet and quaint at best — weakening and painful at worst. […] Well, yes, “gay” is great. It has its place. But when a lot of lesbians and gay men wake up in the morning we feel angry and disgusted, not gay. So we’ve chosen to call ourselves queer. Using “queer” is a way of reminding us how we are perceived by the rest of the world. […] Yeah, queer can be a rough word but it is also a sly and ironic weapon we can steal from the homophobe’s hands and use against him.

Note that Queer Nation acknowledges that “queer” is weaponized against gay people, and that society calls LGBT people “queer” because they viewed them as strange, deviant, and unconventional. Reclaiming the term was a blunt weapon against (cisgender) straight people, an act of defiance (“we’re here, we’re queer, get used to it!”). The historical discomfort behind the word was crucial, in fact, to the momentum of groups like queer Nation. A political movement formed at this time to resist gay rights causes some saw as assimilationist, like same-sex marriage and military inclusion. (I find their manifesto interesting, albeit very neglective of bisexuality.)

A 1995 book on sexual identity notes that in our heterosexist world which enforces “narrow ranges of acceptable male and female behavior… children are affected by the fear of being called ‘queer’ or other words.”

Since the increased reclamation of the slur and usage in LGBT literature, its usage generated controversy. Some argue that it’s created political, social, class, racial, age, and even geographical divides within LGBT communities. In her article, “Don’t call me ‘queer’,” Robin Tyler, one of the first lesbian plaintiffs in the lawsuit that brought same-sex marriage to California, expresses her objections towards the slur:

We are supposed to “reclaim” the word queer — take the sting out of the insult. Never. Many of us spent our lives fighting for lesbian and gay rights and trans rights and bi rights and non-binary rights. We may not remember the pain of the rape or the bang of the baseball bat but we still remember the pain of being called “queer” as the macho-pretenders and the gay bashers beat the crap out of us.

Stephanie Fairyington, a self-identified “queer lesbian,” wrote “The problem with co-opting ‘queer’” for CNN. She points out that while a common identity can generate solidarity:

for many, the word queer still stings. Seventy-eight-year-old lesbian historian Lillian Faderman continues to find it jarring when LGBTQ people of her generation self-identify as queer. “Many men and women of my generation are repelled by the word ‘queer.’ Nothing is going to redeem that word for us because we were so wounded by it in the 50s,” she told me. Fellow historian Jonathan Ned Katz, the 81-year-old author of several books on gay and lesbian history, drove home Faderman’s point in a recent telephone interview. “An old friend who’s in his mid-80s has recently disowned me because in passing, I referred to ‘a queer art show.’ He was deeply, deeply angry and offended and finds it a put-down,” he said.

Many who identify with the slur today are among younger age groups who may not have had this epithet used against them disparagingly. But to say that people no longer use “queer” the way it has been for the past century is ignorant. Away from safer, relatively “liberal” cities (and even in such cities), its use against LGBT people hasn’t faded out at all. In 2016, the Human Rights Watch published a report regarding discrimination and harassment faced by LGBT youth in American schools.

The mother of a gay boy in Utah recalled him being “dragged down the lockers, called ‘gay’ and ‘fag’ and ‘queer,’ shoved into a locker, and picked up by his neck. And that was going on since sixth grade.” After conducting studies in several states, one lesbian in Alabama said: “All the time, I hear slurs. I hear ‘queer’ thrown around a lot, the F word [faggot] thrown around a lot.” Molly from South Dakota described anti-LGBT graffiti she’s encountered at school: “All the bathroom doors in middle school have the F and G [gay] and Q [queer] words written all over them.” Jayden, another gay boy, said: “I’ve had someone yell ‘faggot’ at me, ‘queer boy’...”

“Queer” remains a negative and even traumatizing word to many LGBT people. I reached out to a handful for additional thoughts.

All responses are from 2020. Names are falsified for privacy.

Anna, 22

I hate when people try to be like, “no one’s used it negatively in decades!” as if I wasn’t in middle school having my classmates come up to me and say, “I noticed you don’t date boys, are you a queer?” My gay friend walked on campus and had someone drive by and shout the slur out the window at him this year [2020].

Ash, 26

My homophobic uncle uses the q-slur to describe gay people in front of me and it made me realize I cannot come out to the older generation of my mom’s family. I mean, I’m still gonna come out, but for fuck’s sake, I live in Texas. People say that with hatred on the daily. And so much of the time its used as a way to avoid saying “lesbian,” “gay,” or “bi,” to avoid fully acknowledging us.

Aavani, 16

I hear people going “queer” this and “queer” that and “fuck queers” on a weekly basis in school. I’m tired of hearing that people don’t use it as a slur anymore just because you live in an open environment. That open environment isn’t as open as you think. It’s a bubble.

Brian, 23

I’ve seen many people on the internet claiming that it’s been reclaimed, but in real life, I’ve heard the word many times and exclusively in a hateful context. I, and just about every non-heterosexual person I know, has been called that and absolutely not in an respectful way. I’m not sure how or why some people believe it’s been completely taken back, but in my experiences of having it yelled at me in school when I was seen hugging another boy, it’s just as derogatory and homophobic as it ever was.

Yvette, 19

The q-slur is a severe trigger for me and because of that I dont have access to resources I desperately need. I’ll never be able to take a gender and sexuality studies class, even though I’d really like to otherwise. I tried to sign up for an LGBT mentorship program and the first email they sent me called me the q-slur. They think it’s inclusive but I feel it’s inherently the opposite.

Maria, 20

I was born in Nevada but I only realized I was trans and gay when I was living in North Carolina, so pretty much all of my experiences with growing up with that in mind were when I was in the Bible Belt. I kept to myself really well so I wasn’t ever really bullied, at least for that stuff, but I definitely heard “queer” tossed around as an insult a lot. I’d believe that isn’t as common anymore, especially in more liberal cities, but it’s definitely still used disparagingly, and lots of people have grown up with that, myself included. I’m no longer as uncomfortable with it as I used to be, but I can’t fault people who still are.

Bahiti, 20

I can’t say I have any super negative experiences with the word directly, but it still bothers me to be used against me, especially without my permission. To say it has been “reclaimed” by all of us is at best diminutive. I certainly haven’t. Those who have cannot possibly speak for everyone. That, to me, feels like an attempt to diminish my experiences and worldview, claiming that my opinion on the subject does not matter. I matter just as much as someone with a huge problem with being called queer.

At the same time, I’m a lesbian, and would be uncomfortable with a stranger referring to me as a dyke even though I myself use the word to describe myself frequently. One person and all the people surrounding them accepting it is not enough to assume that I have also accepted the word as an umbrella term.

Grace, 20

My feelings on the slur have always been split, from multiple places of fear and respect at once. It was a word flung casually around my home for anything out of the ordinary, an inconvenience, an unpleasant oddity. The dictionary defined it as “strange,” and so were the people labeled as queer. I grew up knowing that, yes, my bus timetable changing for no reason was “queer,” throwing a wrench in our routine. But so was my cousin, a trans woman, a wrench in our family, an oddity to my relatives.

As I grew up I came to associate it with the LGBT community, and while it had always been a hurtful word to me, an insult from my family though not intentionally LGBT-phobic, I respected the use among other LGBT people. For a year or so in my teens, when I didn’t quite know what I was, I was queer. In my own form of reclamation, repurposing my family’s criticism of everything, I was queer, and that was enough for me.

I grew out of it. As I saw the context of the “queer” change in media and LGBT circles, so did my feelings towards it. “queer” became a weapon again. Not one of self defense, something that comforted me when I didn’t know who I was, but an indirect way of spreading homophobic and transphobic sentiment while still seeming progressive. After all, why would we even use LGBT anymore? queer is so much more inclusive! It’s not a slur, it’s my identity — no way these two concepts can coexist, I guess.

In an attempt to chase maximum progressiveness, somehow homophobia became vogue again, and if you didn’t like being called slurs? Well, sucks to be you. This is the queer community.

To argue that “queer” is somehow not offensive anymore disregards reality and dismisses those still targeted by the slur. We shouldn’t erase the pain it brought upon those before or among us. Individual thoughts and experiences with it don’t erase the harm it has done and continues to do to our community, and claiming otherwise is ignorant and self-centered at best.

“But ‘Gay’ Is a Slur, Too!”

“Autistic” and “fat” are often used disparagingly as well, but that doesn’t make these words slurs. This “counterargument” misunderstands how slurs work. It’s important to not dilute the meaning of this word by using it synonymously with just any “insult.”

Historical context coupled with the oppressor group repurposing the original word specifically to degrade the oppressed, among a few other factors, solidifies a word as a slur. They are — in the words of a (rather interesting) paper examining them (use a Sci-Hub URL to bypass the paywall; I also recommend these four additional papers concerning various linguistic and historical theories surrounding pejoratives) — “prima facie [i.e., based on the first impression; accepted as correct until proved otherwise] associated with the expression of a contemptuous attitude concerning a group of people identified in terms of its origin or descent.”

For instance, “faggot” only used to mean “a bundle of sticks or twigs bound together as fuel,” but over time, heterosexuals began using the word as a way to express demeaning beliefs about LGBT people, primarily man-loving men and transgender women. The word “faggot” brings up a particular set of negative connotations and stereotypes (effeminacy, weakness, perversion, sexual submission, etc.), to the point where some people understand there to be a characteristic difference between (“respectable”) “gays” and (“contemptible”) “faggots.” The word itself is the insult. The derogatory force is also independent of its speakers’ beliefs.

The counterargument that “gay” is somehow as much of a slur as “queer” makes little sense. Although quite a few heterosexuals do use “gay” as an insult, history, general intent, and original definitions matter as well. Calling a black person an ape is undoubtedly racist, but “ape” isn’t necessarily a racial slur.

“Gay,” derived from the Old French “gai,” first meant “joyous,” “happy,” and “pleasant.” The first time people used it in a negative context was arguably in the 1300s, where “gay women” were sex workers, “gay houses” were brothels, and “gay men” were men who partook in numerous sexual affairs with women. “Gay” thus had some ties with promiscuity.

Towards the end of the 1600s, the word became linked with sex work. “Gay boy” now meant a male sex worker who took male clients. The association with (modern-definition) gayness likely got a push from the late nineteenth-century term “gay cat,” which described young homeless men who typically took odd jobs. But these still wouldn’t necessarily count as the beginnings of its use as an insult specifically towards gay men — the only connection the word had to “gay” men was via sex work, and many (if not most) male sex workers are heterosexual.

It also still meant “joyous,” “happy,” and “carefree” as the centuries went on, as revealed by terms like “gay bachelor,” referring to a middle-aged, unmarried man. The 1934 film The Gay Divorcee was about a heterosexual couple.

The Dictionary of American Slang (1960) reports that actual gay folks used “gay” among themselves since the 20s. One of the first recorded uses of the word “gay” to refer to a(n allegedly) same-sex attracted person was in the 1938 film Bringing Up Baby. In one scene, a man is forced to wear a feather-trimmed robe and explains it by saying, “I just went gay all of a sudden.” However, film critics of the time assert that his line simply meant he wanted to do something flippant. Whether or not that phrase explicitly identified the character as a gay man remains debatable.

Some psychological texts from the late 40s start showing signs of “gay” as a synonym for “homosexual,” evidently adopted from gay male slang:

After discharge A.Z. lived for some time at home. He was not happy at the farm and went to a Western city where he associated with a homosexual crowd, being “gay,” and wearing female clothes and makeup. He always wished others would make advances to him. [Rorschach Research Exchange and Journal of Projective Techniques, 1947, p. 240]

It’s relatively unclear, however, whether “gay” refers to A.Z.’s sexuality, his femininity, or something else.

The first clear-as-day recorded use of “gay” as a synonym for “homosexual” from a self-identified gay man was in 1950. Alfred A. Gross wrote in an issue of Sir magazine:

I have yet to meet a happy homosexual. They have a way of describing themselves as gay but the term is a misnomer. Those who are habitues of the bars frequented by others of the kind, are about the saddest people I’ve ever seen.

Even in this otherwise gloomy passage, we see that “gay” still had primarily positive connotations. Still, it wasn’t yet the common word of the public to refer to gay men — who chose the term “gay” on their own accord without any push from heterosexuals. From the 60s onward, it began to refer to gay people on a wider scale as early LGBT activists began rejecting the term “homosexual” due to its medical contexts.

An article in a 1977 issue of the Bay Area Reporter provides some insight from this time:

Non-homosexuals — or “straight” people, as Gay people call them — are inclined to believe that the word “gay” has always in the past meant happy, merry, lively, bright. Straight people say that they don’t understand now such a “nice” word has acquired the special homosexual meaning which is now so commonly used by both homosexuals and the public media.

A well-known San Francisco columnist has asked on several occasions, “Why do they call them Gay when so many of them aren’t?” And a commentator on National Public Radio has complained about what he thinks is a perversion of the meaning of “gay”: “No self-respecting person feels safe using the word any longer,” he says in a tone that lets his listeners know that he feels unfairly put-upon. These are but two expressions of recent confusion about what is assumed to be a new and unusual use of the word.

“Gay,” as homosexuals use the term, has generally come into public use only since the late 1960’s — that is, since the formation of an active Gay liberation movement. It was known and used by homosexuals, of course, long before that time, although they kept their special meaning pretty much to themselves. It was part of the secret life which homosexuals were obliged to live. This is not to say, however, that Gay people have been any more informed about the source of the term than many straight people are at present. For a good many years, the double meaning of the term has brought humor to Gay situations, but it has also brought unanswered questions about what the term really means.

In spite of the present confusion, the word “Gay,” in its homosexual context, has a long and respectable history.

Interestingly, at this time, the word “gay” also explicitly included bisexuals:

Homosexual is the label that was applied to Gay people as a device for separating us from the rest of the population. . . . Gay is a descriptive label we have assigned to ourselves as a way of reminding ourselves and others that awareness of our sexuality facilitates a capability rather than creating a restriction. It means that we are capable of fully loving a person of the same gender. . . . But the label does not limit us. We who are Gay can still love someone of the other gender.

Its use as an insult connected to gayness started in the late 70s, and in the following decades, phrases like “that’s so gay” in negative contexts became common. Many people still use the word this way, and it’s obviously homophobic. But the word “gay” as a jibe, unlike “queer,” wasn’t used to directly target gay people; rather, its use here expresses that something is undesirable by comparing it to them. It’s essentially akin to someone calling me “black” to insult me, or disparagingly calling a book “transgender” or a woman “fat.” There’s no history of “gay” being an actual slur.

“Gay” was a self-chosen label that gained unfavorable implications due to its association with gay people. “Queer” has had negative connotations since the word came into existence, and has been used by cisgender heterosexuals with the express purpose of describing LGBT people in an insulting manner.

“Are You Saying No One Should Use ‘Queer’ Ever?”

No. Many LGBT people find safety, comfort, and pride in queerness. It can be valuable and sentimental to some. Considering that some LGBT people — including myself — refer to their identities with other slurs like “faggot,” to say that “queer” is an extraordinarily special case would be unfair and hypocritical. There’s nothing wrong with simply identifying with a politically loaded word. “queer” has its place. The word can be offensive, yes, but that’s true for all slurs, and reclaiming them can be a coping mechanism or a political decision, a way to say, “yes, I am what you say — so what?”

Still, there will always be people who will remain uncomfortable with it. Regardless of how widely reclaimed a slur is, there are still people that word targets who don’t like hearing it and don’t want it used on them. Even if most people in a community reclaim a slur, that doesn’t mean all of them are automatically okay with it. Nobody can make an executive decision that a slur is no longer such because others will disagree. The word will always have historical relevance.

While its usage depends on one’s environment, it’s arguably a privileged position to be in where one can forcibly label an entire demographic with a slur (particularly around individuals who explicitly express discomfort with that) while many can’t escape the violence behind it. Nobody calls man-loving men and transgender women “the faggot community,” even though we may politically and proudly reclaim that word. Simply because many women attend Dyke Marches doesn’t mean that word isn’t still hurtful to many others (including some participants). Why would it be different with “queer”?

With how loaded the word still is for many, calling other LGBT people “queer” without knowing if they’re okay with that isn’t reclamation, it’s just disrespectful. Reclamation cannot be done as a collective. The insistence that “queer” is more inclusive than LGBT as an umbrella term is backwards; it excludes, dismisses, and isolates every LGBT person who doesn’t reclaim it.

Quite a few LGBT people feel uncomfortable attending LGBT events or even reaching out to LGBT strangers due to being called “queer.” For a growing mindset of letting people identify as they please, forcing terms onto others so insistently seems almost regressive.

I also find it potentially hazardous that so many cisgender heterosexuals now use “queer” without knowing its history, even thinking it’s the respectful option. Many still use it the degrading way they did before it gained today’s popularity among LGBT people. Reclamation shouldn’t permit oppressors to use it, especially considering they were the ones who transformed the word into a slur in the first place.

As someone who’s been happily calling himself a fag for years, I will never understand why some people would refuse to acknowledge that “queer” is a slur or, by extension, say (if they identify as queer) that “their identity is not a slur.” One cannot separate history from the names used to describe their identity. To do so denies their political history. Why would one even want to disarm a word as (at least intentionally) inflammatory as “queer”?

I enjoy reclaiming “faggot” because that word has a violent history against me and my community. It feels good to take it back and bring them into my power, my control. But this pleasure only comes with the fact that these words harm me still. One can’t “reclaim” a word in this sense that we talk about if it isn’t a slur. Then it’s just another word. Are we willing to strip “queer” of its legacy — of queer rage, of defiance against normativity — to make it “just another word”?

I’m additionally baffled by those obsessed with the idea of “normalizing” the word “queer,” thinking we can completely eliminate its oppressive power (which inherently rids it of its otherwise radical nature) just by shoving it in the mainstream enough. I can hardly articulate how arrogant it seems to believe that’ll ever happen before we fully eliminate heterosexism, the source of this word’s political influence.

No issues will be solved just by trying to train people to not care about having epithets thrown at them, because regardless of what meaning we give it, the reason bigots use it didn’t change. As long as there are homophobes on this Earth who use it as a weapon, as long as there are LGBT people who thus have trauma with that word, it will have oppressive power.

To Wrap Up

At some point, this is just a matter of self-awareness and honoring boundaries instead of prioritizing yourself over the people you hurt. If an LGBT person has had “queer” used against them and doesn’t want it used to group in their identity, others shouldn’t see that as a personal affront. They should respect the request, just as much as one should honor when someone doesn’t want to be called an “asshole,” even by friends, or when a transgender person doesn’t want to be called their birth name.

It’s very much still a sensitive term, regardless of one’s relationship with it. “Reclamation” does not mean “divorcing something from its history.” LGBT folks, respect other people’s limits; be mindful of who you use it around and in which contexts. (And it may not be the best idea to call dead LGBT people slurs if there’s no historical evidence of them identifying with those slurs.)